|

|

|

|

IT MAY THUS be seen that warnings were not wanting. I give now another trait, more striking than either of those just related, copied from a journal published at Green Bay.3 It is a description of a combat sustained against the terrible element of fire at Peshtigo, Sunday, September 24, just two weeks before the destruction of the village:

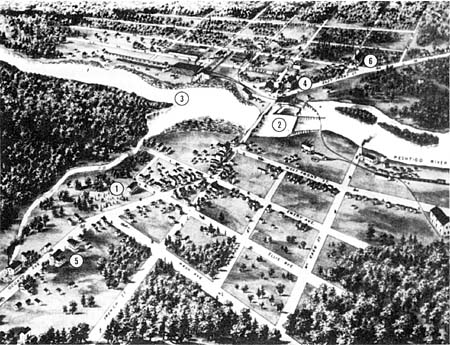

What did these repeated alarms filling the minds of the people with anxiety during the three or four weeks preceding the great calamity seem to indicate! Doubtless they might have been looked on as the natural results of the great dryness, the number of fires lighted throughout the forests by hunters or others, as well as of the wind that fanned from time to time these fires, augmenting their strength and volume, but who will dare to say that they were not specially ordained by Him who is master of causes as well as of their effects? Does He not in most cases avail Himself of natural causes to execute His will and bring about the most wonderful results? It would indeed be difficult for anyone who had assisted as I had done at the terrible events following so closely on the above mentioned indications not to see in them the hand of God, and infer in consequence that these various signs were but forerunners of the great tragedy for which He wished us to be in some degree prepared. I cannot say whether they were looked on by many in this light or not, but certainly some were greatly alarmed and prepared as far as lay in their power for a general conflagration, burying in the earth those objects which they specially wished to save. The Company caused all combustible materials on which a fire could possibly feed to be taken away, and augmented the number of water hogsheads girdling the town. Wise precautions certainly, which would have been of great service in any ordinary case of fire but which were utterly unavailing in the awful conflagration that burst upon us. They served nevertheless to demonstrate more clearly the finger of God in the events which succeeded. As for myself, I allowed things to take their course without feeling any great anxiety as to consequences, or taking any precautionary steps, a frame of mind very different to that which I was destined to experience on the evening of the eighth of October. A word now about my two parishes. Peshtigo is situated on a river of that name, about six miles from Green Bay with which it communicates by means of a small railroad. The Company established at Peshtigo is a source of prosperity to the whole country, not only from its spirit of enterprise and large pecuniary resources but also from its numerous establishments, the most important of which, a factory of tubs and buckets, affords alone steady employment to more than three hundred workmen. The population of Peshtigo, including the farmers settled in the neighborhood, numbered then about two thousand souls. We were just finishing the construction of a church looked on as a great embellishment to the parish. My abode was near the church, to the west of the river, and about a five or six minute walk from the latter. I mention this so as to render the circumstances of my escape through the midst of the flames more intelligible. |

||

Peshtigo before the fire |

||

|

Besides Peshtigo, I had the charge of another parish much more important situated on the River Menominee, at the point where it empties into Green Bay. It is called Marinette, from a female half breed, looked on as their queen by the Indians inhabiting that district. This woman received in baptism the name of Mary, Marie, which subsequently was corrupted into that of Marinette, or little Marie. Hence the name of Marinette bestowed on the place. It is there that we are at present building a church in honor of our Lady of Lourdes. At the time of the fire, Marinette possessed a church, a handsome new presbytery just finished, in which I was on the point of taking up my abode, besides a house in course of construction, destined to serve as a parish school. The population was about double that of Peshtigo. |

||

"Queen Marinette" and her home |

||

|

Before entering into details, I will mention one more circumstance which may appear providential in the eyes of some, though brought about by purely natural causes. At the time of the catastrophe our church at Peshtigo was ready for plastering, the ensuing Monday being appointed for commencing the work. The lime and marble dust were lying ready in front of the building, whilst the altar and various ornaments, as well as the pews, had all been removed. Being unable in consequence to officiate that Sunday in the sacred edifice, I told the people that there would be no mass, notifying at the same time the Catholics of Cedar River that I would spend the Sunday among them. The latter place was another of my missions, situated on Green Bay, four or five leagues north of Marinette. Saturday then, October 7, in accordance with my promise, I left Peshtigo and proceeded to the Menominee wharf to take passage on the steamboat Dunlap. There I vainly waited her coming several hours. It was the only time that year she had failed in the regularity of her trips. I learned after that the steamboat had passed as usual but stood out from shore, not deeming it prudent to approach nearer. The temperature was low, and the sky obscured by a dense mass of smoke which no breath of wind arose to dispel, a circumstance rendering navigation very dangerous especially in the neighborhood of the shore.4 Towards nightfall, when all hope of embarking was over, I returned to Peshtigo on horseback. After informing the people that mass would be said in my own abode the following morning, I prepared a temporary altar in one of the rooms, employing for the purpose the tabernacle itself which I had taken from the church, and after mass I replaced the Blessed Sacrament in it, intending to say mass again there the next Monday. In the afternoon, when about leaving for Marinette where I was accustomed to chant vespers and preach when high mass was said at Peshtigo, which was every fortnight, my departure was strongly opposed by several of my parishioners. There seemed to be a vague fear of some impending though unknown evil haunting the minds of many, nor was I myself entirely free from this unusual feeling. It was rather an impression than a conviction, for, on reflecting, I saw that things looked much as usual, and arrived at the conclusion that our fears were groundless, without, however, feeling much reassured thereby. But for the certainty that the Catholics at Marinette, supposing me at Cedar River, would not, consequently, come to vespers, I would probably have persisted in going there, but under actual circumstances I deemed it best to yield to the representations made me and remain where I was. God willed that I should be at the post of danger. The steamboat which I had expected to bear me from Peshtigo, on the seventh of October, had of course obeyed the elements which prevented her landing, but God is the master of these elements and Him they obey. Thus I found myself at Peshtigo Sunday evening, October 8, where, according to all previous calculations, projects, and arrangements, I should not have been. The afternoon passed in complete inactivity. I remained still a prey to the indefinable apprehensions of impending calamity already alluded to, apprehensions contradicted by reason which assured me there was no more cause for present fear than there had been eight or fifteen days before--indeed less, on account of the precautions taken and the numerous sentinels watching over the public safety. These two opposite sentiments, one of which persistently asserted itself despite every effort to shake it off, whilst the other, inspired by reason was powerless to reassure me, plunged my faculties into a species of mental torpor. In the outer world everything contributed to keep alive these two different impressions. On one side, the thick smoke darkening the sky, the heavy, suffocating atmosphere, the mysterious silence filling the air, so often a presage of storm, seemed to afford grounds for fear in case of a sudden gale. On the other hand the passing and repassing in the street of countless young people bent only on amusement, laughing, singing, and perfectly indifferent to the menacing aspect of nature, was sufficient to make me think that I alone was a prey to anxiety, and to render me ashamed of manifesting the feeling. During the afternoon, an old Canadian, remarkable for the deep interest he always took in everything relating to the church, came and asked permission to dig a well close to the sacred edifice so as to have water ready at hand in case of accident, as well as for the use of the plasterer who was coming to work the following morning. As my petitioner had no time to devote to the task during the course of the week, I assented. His labor completed, he informed me there was abundance of water, adding with an expression of deep satisfaction: "Father, not for a large sum of money would I give that well. Now if a fire breaks out again it will be easy to save our church." As he seemed greatly fatigued, I made him partake of supper and then sent him to rest. An hour after he was buried in deep slumber, but God was watching over him, and to reward him doubtless for the zeal he had displayed for the interests of his Father's House, enabled the pious old man to save his life; whilst in the very building in which he had been sleeping more than fifty people, fully awake, perished. What we do for God is never lost, even in this world. Towards seven in the evening, always haunted by the same misgivings, I left home to see how it went with my neighbors. I stepped over first to the house of an elderly kind-hearted widow, a Mrs. Dress, and we walked out together on her land. The wind was beginning to rise, blowing in short fitful gusts as if to try its strength and then as quickly subsiding. My companion was as troubled as myself, and kept pressing her children to take some precautionary measures, but they refused, laughing lightly at her fears. At one time, whilst we were still in the fields, the wind rose suddenly with more strength than it had yet displayed and I perceived some old trunks of trees blaze out though without seeing about them any tokens of cinder or spark, just as if the wind had been a breath of fire, capable of kindling them into a flame by its mere contact. We extinguished these; the wind fell again, and nature resumed her moody and mysterious silence. I re-entered the house but only to leave it, feeling restless, though at the same time devoid of anything like energy, and retraced my steps to my own abode to conceal within it as I best could my vague but continually deepening anxieties. On looking towards the west, whence the wind had persistently blown for hours past, I perceived above the dense cloud of smoke overhanging the earth, a vivid red reflection of immense extent, and then suddenly struck on my ear, strangely audible in the preternatural silence reigning around, a distant roaring, yet muffled sound, announcing that the elements were in commotion somewhere. I rapidly resolved to return home and prepare, without further hesitation, for whatever events were impending. From listless and undecided as I had previously been, I suddenly became active and determined. This change of mind was a great relief. The vague fears that had heretofore pursued me vanished, and another idea, certainly not a result of anything like mental reasoning on my part, took possession of my mind; it was, not to lose much time in saving my effects but to direct my flight as speedily as possible in the direction of the river. Henceforth this became my ruling thought, and it was entirely unaccompanied by anything like fear or perplexity. My mind seemed all at once to become perfectly tranquil. |

||

3 The account is from the Green Bay Advocate, October 5, 1871.

4 During early October the smoke was so dense on the Bay that during daylight hours navigation was done by compass, and fog horns were kept blowing continuously, the shores being invisible. Green Bay Advocate, October 5, 1871.