|

|

|

EpilogueFROM PESHTIGO the fire roared toward Marinette, destroying Father Pernin's other church and its newly built presbytery, but leaving the village mainly intact. Then the fire split into two forks, the one on the right going on to consume the village of Menekaunee, the one on the left jumping the Menomonee River to ravage the Birch Creek settlement in Michigan, killing eight men, two women, and twelve children. Some sources have estimated the number of dead as 1,200. The Encyclopedia Britannica gives a total of 1,152, evidently using the figure arrived at by Stewart Holbrook in his Burning An Empire. However, the true total will never be known, since whole farmsteads were erased, leaving no trace, and no one knows how many itinerant workers died in Peshtigo's company boarding house or in its two churches to which many fled in panic, or in isolated logging camps deep in the surrounding woods. People simply became piles of ashes or calcinated bones, identifiable only if a buckle, a ring, a shawl pin or some other familiar object survived the incredible heat. A painstaking, three-month investigation by Colonel J. H. Leavenworth, as printed in the Assembly Journal for 1873, lists the names of only 383 identified dead: 77 in Peshtigo, 12 in Lincoln, 50 in Brussels, 3 in Nasawanpee, and 22 in Birch Creek, Michigan. The heaviest losses were in the Sugar Bushes, where no convenient river furnished a refuge from the flames. Here a total of 241 identified bodies were found, of whom 123 were those of children. How many died subsequently or were maimed for life is not known. At any rate, according to Leavenworth's report, a year after the event many survivors remained partially or permanently demented as a result of their ordeal. News of the disaster did not immediately reach the outside world. Isaac Stephenson, the Marinette lumber baron, on learning of Peshtigo's fate, had an emissary sent to Green Bay--the nearest place where the telegraph lines had not been burned out--to transmit a message to Governor Lucius Fairchild. The message did not reach Madison until the morning of the 10th. Fairchild and all state officials were in Chicago, whence they had gone with carloads of supplies to aid the stricken city. A capitol clerk took the telegram to Mrs. Fairchild, who immediately swung into action. For a day this remarkable woman, then less than twenty-four, was to all intents and purposes the governor of Wisconsin. As her daughter, Mrs. Mary Fairchild Morris, recalled in a letter to Joseph Schafer in May, 1927, her mother commandeered a boxcar loaded with supplies destined for Chicago, ordered railroad officials to give it priority over all other traffic, and then discovering that the car contained food and clothing but no defenses against the October cold, rallied Madison women to supply blankets to stuff into the already loaded car. After the car was dispatched, Mrs. Fairchild issued a public appeal for contributions of money, clothing, bedding, and supplies, with the result that a second boxcar left Madison that night. |

||

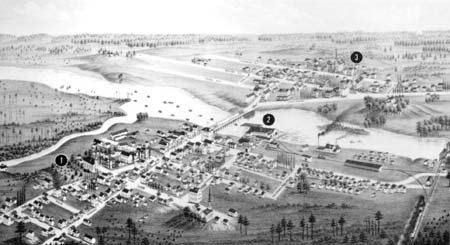

Peshtigo rebuilt, 1881 |

||

| Immediately on receiving the news of the Peshtigo disaster, relief committees

were organized in Green Bay, Oconto, and Marinette; emergency hospitals

were set up for the injured, and lodgings were found for the homeless survivors.

Eventually the Green Bay Relief Committee was augmented by a second in Milwaukee,

and hardly a community in the state failed to establish some kind of relief

organization. Following Governor Fairchild's broadcast appeal for aid, contributions

began to pour in from all over the state, the nation, and several foreign

countries. In all, $166,789 was collected in cash donations, while the United

States government contributed from army supplies 4,000 woolen blankets,

1,500 pairs of trousers and overcoats, 100 wagons with sets of harness,

and 200,000 rations of hard bread, beans, bacon, dried beef, pork, sugar,

rice, coffee and the like.

Slowly the devastated area began to recover. Schoolhouses and bridges were rebuilt, roads were repaired. Despite his substantial losses, William G. Ogden ordered that his wooden-ware company be rebuilt; others followed suit, and Peshtigo struggled back to life. In January, 1873, Governor Cadwallader C. Washburn, who had succeeded Lucius Fairchild, reported in the Assembly Journal: "In the month of July I visited the burnt district on the penninsula, as well as on the west side of Green Bay. I found the devastation produced by the fire fiend such as is impossible for the mind to comprehend without the aid of the eye. I was pleased to find that a majority of the survivors had returned to their clearings; many had raised fair crops, and were hopeful of the future. . . ." Part of the process of reconstruction included the rebuilding of Father Pernin's church, Our Lady of Lourdes. It still stands today on Main Street in Marinette as a part of Central Catholic High School, its sanctuary serving as a chapel and the remainder of the building as a rehearsal hall. |

||